1. INTRODUCTION

The generation tariff is simply the wholesale cost of electricity or the rate at which Generation Companies (GenCo) sell power to Distribution Companies (DisCo). In today’s article, we will be taking a deep dive into the generation tariff in the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry (NESI) value chain. We will begin by discussing the cost of generation under different market structures, and pricing models in a wholesale electricity market. We will then focus on the cost of wholesale electricity in Nigeria and the drivers of this cost.

2. GENERATION TARIFF

To raise financing to build a power plant, the GenCo must provide a bankable contract to its financiers that it has off-takers for the electricity to be generated from the plant. The contract it has with the off-takers is known as the power purchase agreement (PPA). The financing raised will include the capital cost of building the power plant, a component of the operating costs incurred regardless of power supply, and the cost of financing.

GenCo will have a fuel supply agreement to operate a fuel-based power plant that mirrors the PPA’s contractual energy volumes and associated fuel costs. Other costs incurred are the costs of operating and maintaining the power plant which are proportional to the power supplied, including personnel and spare parts.

All these costs make up the wholesale cost of electricity, known in some markets as the generation tariff.

2.1. Generation Tariff and Market Structures

The two main market structures that exist in the electric industry are:

- Regulated/Traditional Electricity Market (Typically a Vertically Integrated Electric Utility)

- Deregulated/Restructured Markets

2.1.1. Cost of Generation in a Vertically Integrated Electric Utility (VIEU)

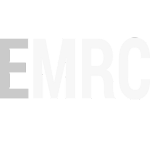

In a typical VIEU, all the value chain sectors are owned and controlled by one entity. This entity, which may be government-owned or private, manages generation transmission and distribution to deliver electricity to all customers within a particular region. A good example of a VIEU is the now-defunct National Electric Power Authority (NEPA) which provided electricity generation, transmission, and distribution services across Nigeria.

Where one entity is in control, a single cost that represents the entire value chain is passed to customers. Customers, therefore, purchase electrical energy directly from the power utility through the distribution company.

2.1.2. Cost of Generation in a Deregulated Market

The transition from traditional power network structures has seen the evolution of power markets with different market participant competition models namely, the purchasing agency, wholesale competition, and retail competition.

In the purchasing agency model “SingleBuyer Model”, the vertically integrated company is disaggregated and sees GenCos sell their energy directly to a wholesaler, who in turn sells the energy to private DisCos; with the government standing as a guarantor for the wholesaler to ensure that the GenCos are compensated for their services. A regulator determines the energy rates established by the wholesaler to ensure energy cost minimisation for customers. In this structure, competition exists only among the GenCos. This is Nigeria’s current market structure where the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading (NBET) Plc buys power from the generators and sells it to the DisCos.

In the wholesale competition structure, the wholesaler entity is absent, with energy purchases occurring directly between DisCos and GenCos. A higher level of competition occurs in this structure between GenCos as energy prices are determined solely by the market interaction of demand and supply, while distributed energy prices remain regulated.

In the retail competition structure, which has the highest level of competition, retailers purchase energy directly from generators and sell to their customers, while using the distribution and transmission infrastructure for energy supply. The distribution and transmission networks function as monopolies providing energy supply services, with usage fees paid by the retailers.

2.2. Electricity Pricing Models

There are 3 main pricing models used by countries in setting electricity prices:

I. National Pricing – This is characterised by the existence of one wholesale price of electricity which is obtainable across the entire geographical region of the market. This is currently used in the UK and Nigeria.

II. Zonal Pricing – Here, the transmission system is split into several geographical regions or “zones” with each zone having a different wholesale electricity price. This is used in countries such as Australia, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Italy which has 6 pricing zones.

III. Nodal Pricing – This is also known as Locational Marginal Pricing (LMP). Here, the national grid is divided into hundreds and even thousands of nodes with separate wholesale electricity prices. In the state of California where nodal pricing is practised, there are over ten thousand nodes.

3. THE GENERATION TARIFF IN NIGERIA

3.1. The NESI Market Structure

The electricity supply industry in Nigeria is no longer a VIEU. The sector is currently transitioning to a retail market where prices will be determined competitively.

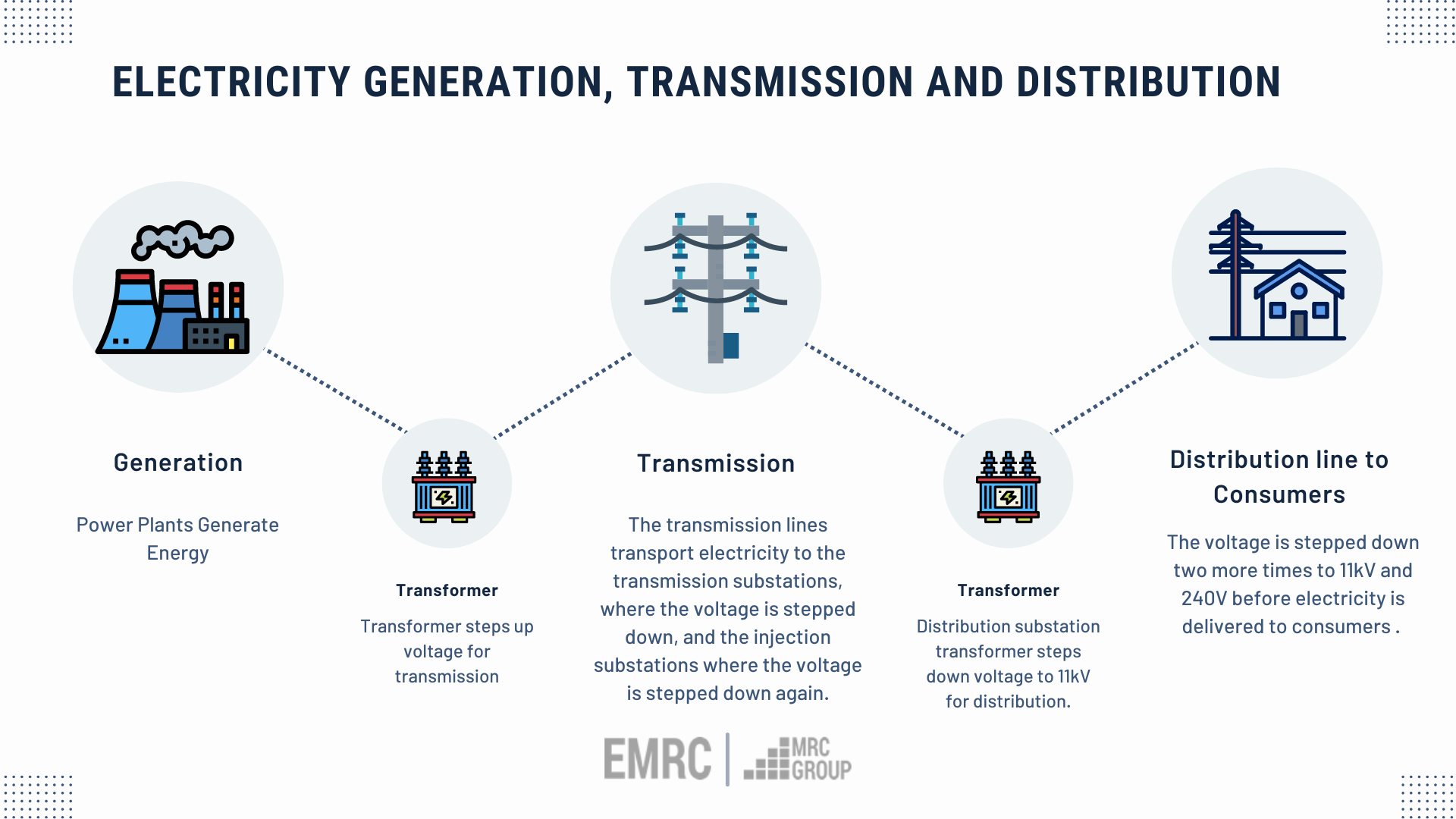

As a transitional market, Nigeria has adopted the Single Buyer Model. Under the NESI Market Rules, each GenCo should have a PPA with NBET which is fully government-owned and NBET, in turn, should have Vesting Contracts (VCs) with each DisCo for the sale of the units it procures from the GenCos. Consequently, NBET procures electricity in bulk from the GenCos and sells it to the DisCos.

For contractual alignment, the VCs entered between NBET, and DisCos must mirror the PPA terms between NBET and GenCos. Therefore, all commercial terms in the VCs will be the same for all DisCos except for offtake volumes “load allocation”. The load allocation has been determined by the regulator and is an indication of the total customer demand of each DisCo. This means that the unit cost of procuring wholesale power from a particular power plant must be the same across the country. Hence, if the wholesale cost of power from GenCo A is N10, all DisCos must pay N10 for each unit they receive.

The purpose of these contracts is to provide certainty in the cost of generation as the market becomes competitive. With these contracts, DisCos can hold GenCos accountable for providing a predetermined amount of energy and capacity, and where they fail to do so, DisCos will be entitled to liquidated damages. On the other hand, where the GenCos meet their obligations, but the power is not utilised by the DisCo, the DisCo will still be required to pay for the energy they did not utilise. This arrangement is often referred to as a Take-or-Pay agreement.

However, only five GenCos have active take-or-pay PPAs. One reason for this is that power plants in Nigeria have a combined generation capacity of about 13,400MW but the transmission network can only reliably transport just over 5,000MW of electricity. Therefore, NBET cannot procure electricity it cannot supply to DisCos.

Another reason for this is due to current market illiquidity and operating losses which means DisCos are unable to pay for all their delivered power. If DisCos are unable to meet their payment obligations to NBET, GenCos with PPAs will need to be settled and may result in the unwanted event of the Federal Government being forced to settle the shortfall. To manage this risk, few GenCos have active take-or-pay PPAs with NBET.

Where there is no active take-or-pay PPA between the GenCos and NBET, the GenCos have no contractual capacity obligations to DisCos and vice versa, which ultimately leads to low electricity generation and low energy offtake by DisCos.

The GenCos simply inform the DisCos of their available capacity, which the DisCos consent to receive, and a DisCo is only required to pay for the energy and capacity equivalent of the supply delivered

3.2. The Generation Tariff and NERC

In compliance with S76 of the Electric Power Sector Reform Act (EPSRA) which empowers the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) to adopt the tariff methodology for NESI, the prices in the PPAs between NBET and GenCos are approved by NERC. This ensures that the cost of generation passed down to the final consumer is fair and prudent. NERC sets the generation tariff in Nigeria using the Long Run Marginal Cost (LRMC) method.

3.2.1. The Long Run Marginal Cost (LRMC) Method

Power plants do not last forever. They have lifespans, and entities who invest in power plants are typically rewarded with a return on their investments over the lifespan of the power plant. Therefore, to determine the generation tariff, NERC considers all the costs that are required to efficiently run a new power plant over its life span. These costs include the current cost of the generation plant and equipment, return on capital, operation and maintenance, cost of fuel, and other necessary costs.

The LRMC method which covers short terms costs such as fuel and operations as well as long-run return on investments to ensure efficiency is applied in two ways depending on the generation plant:

1. Benchmark costing – This is automatically applied to the 6 GenCos that existed before the NESI was privatised. Under the benchmark costing, NERC uses the LRMC of a new and cost-efficient power plant to set the generation tariff.

2. Individual LRMC for each generator – This method applies to any new independent power producer (IPP) that requires a tariff above the benchmark cost. Here, NERC sets a price for the individual generation company based on costs specific to the power plant and site.

To obtain an individual LRMC, an IPP will be required to submit their plans, accounts, and financial models to NERC for scrutiny, following which NERC will determine whether the entire proposed plant costs should be allowed in the tariff. This means that the wholesale price of electricity may differ between generation companies.

Currently, the benchmark LRMC is determined based on the lowest cost of a new Open Cycle Gas Turbine (OCGT) which uses natural gas. According to NERC, the OCGT was chosen because most of the new and planned power plants in Nigeria at the time of the decision, were OCGTs and because natural gas is the most environmentally friendly and abundant fuel in Nigeria.

Thus, we can say that the benchmark generation tariff or cost as applied in the NESI involves estimating a price that will allow a new OCGT plant to recover all costs over its lifetime.

3.3. Capacity and Energy Charges

While the value of the wholesale price of electricity may differ among GenCos, the components of that wholesale cost are the same, as follows:

1. The Capacity Charge

2. The Energy Charge.

3.3.1. The Capacity Charge

When a power plant is built, the capital expenditure and return on investment must be paid for through energy sales. The capacity charge is made up of the capital recovery charge which includes the investment cost, financial returns, and taxes. The capacity charge also includes the fixed operations and maintenance charges which cover the plant’s fixed costs including plant maintenance, spare parts, and insurance. The average capacity charge from the July 2022 Tariffs is 13.59 N/kWh.

3.3.2. The Energy Charge

The energy charge accounts for the cost of power that is generated and sent out to during a specific period. It consists of fuel costs and variable operation and maintenance costs that are dependent on the volume of energy produced. The average energy charge from the July 2022 Tariffs is 14.89 N/kWh.

While the energy and capacity charges for each power plant are the same across the DisCos, their generation bills may differ due to their individual load allocation. This means that a DisCo that receives 600MW of electricity will pay a higher total generation cost than another which receives 300MW of electricity.

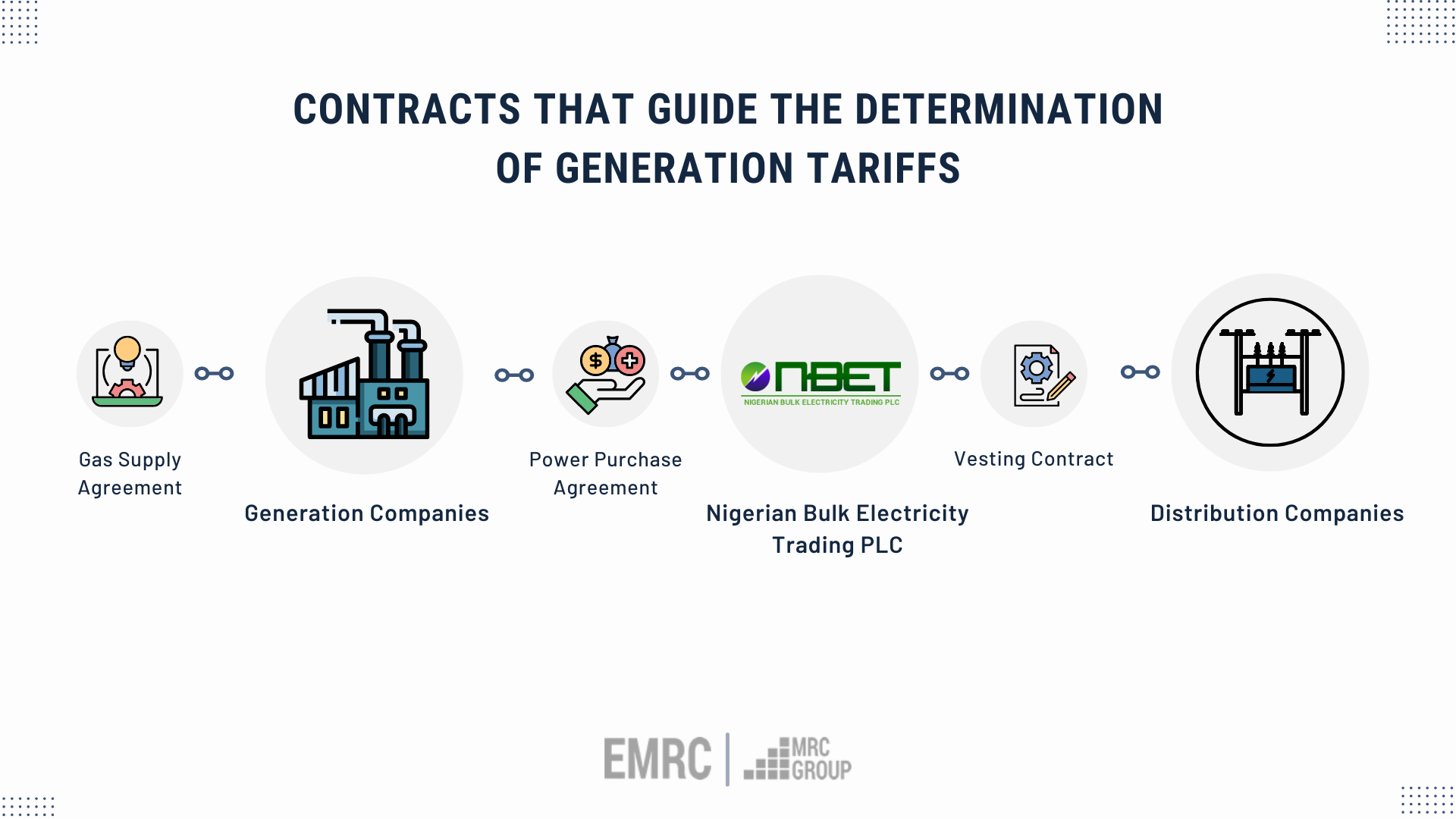

The final cost of generation that DisCos’ pay is based on a generation price efficiency mechanism used by NERC called the Economic Merit Order Dispatch (EMOD). The average generation price from the July 2022 Tariffs is 28.48 N/kWh.

3.4. The Economic Merit Order Dispatch Price (EMOP)

The Economic Merit Order Dispatch (EMOD) is a mechanism for achieving efficiency in NESI by minimising generation costs. This is done by utilising/dispatching the cheapest generators to meet DisCo demand before those with higher prices.

The capacities to be dispatched from each generator by the System Operator (SO) is set by NERC. The total generation capacity is set to equal the total demand of the DisCos. The hydroelectric plants, which are cheap due to the absence of fuel costs, are dispatched first. Next to be dispatched are the thermal plants with active take-or-pay PPAs, and then followed by the rest of the generators in order of cost and system technical requirements.

By setting the dispatch capacity and price of each generator, NERC effectively sets an average price of generation for NESI. This average price known as the EMOD Price provides a deviation allowance of +1.75% by the SO.

The Economic Merit Order Guidelines, released in 2020, outlines a methodology to account for deviations from the EMOD by the SO/TCN. In summary, it provides that when there is an “unfavourable deviation from the EMOD”, TCN would be penalised for the difference between the actual average generation price and the EMOD Price.

By allowing for this penalty, NERC incentivises the SO to ensure the lowest wholesale cost of generation in its dispatch activities. The total penalty incurred by the SO for 2020 was N11.4bn.

Tariff reviews which allow for updates in generation prices occur every six months, however, DisCos pay for the cost of generation monthly. Therefore, if the actual average generation price is higher than the EMOD Price in the end-user tariffs, DisCos will incur revenue shortfalls until the next tariff review. The EMOD penalty is therefore compensated to DisCos to account for revenue shortfalls due to the generation price.

See copy here

4. CONCLUSION

Much thought and consideration go into the generation tariff determination process. However, customers in the NESI still lack access to stable and reliable power. So, with all the initiatives in place that currently guide generation supply and power costs, why do customers not receive reliable supply?

Power supply constraints along the value chain include unavailable generation assets, gas supply, hydro reservoir management, transmission infrastructure and distribution network limitations, meaning that only about 4,000MW (30%) of Nigeria’s installed generation capacity of 13,400MW can be reliably delivered to DisCo customers.

Market liabilities have hindered NBET’s ability to sign new PPAs to procure additional power. Aggregate losses of DisCos of around 50% currently impair their ability to settle their NBET bills; with only about 40-60% settlement performance.

The Single Buyer model also denies possible direct financial collaboration between DisCos and GenCos to generate resources to improve operational efficiency along bilateral value chains.

Nevertheless, in July 2022, NERC partially activated the PPAs between NBET and additional GenCos such that each GenCo is currently obligated to always make a certain percentage of their capacity available and where they fail to do so, they will pay liquidated damages to NBET.

And where DisCos fail to offtake the contracted capacities, those capacities will be paid for in full. This initiative should see the total capacity delivered to DisCos increase by about 20% to 4,790MW.

The implementation of the performance improvement plans (PIPs) of DisCos which details their efficiency and service improvement programs, should see the elimination of distribution network constraints, and an increase of supply to end-user customers.

The Federal Government’s Presidential Power Initiative in collaboration with Siemens has been designed to resolve transmission, distribution and fuel supply constraints and increase end-to-end power supply throughput to 7,600MW in its medium-term plan.

Finally, at a more mature stage when NESI adopts a wholesale competition structure, NBET’s PPA obligations with the GenCos, will be transferred to DisCos, as NBET is phased out of the market.

In the next part of our tariff series, we will consider the costs associated with the transmission sector of the NESI value chain.