Introduction

There is a price associated with most goods and services. This price may not be borne by the consumers but may be covered either in part or in full, by other entities such as governments and charitable entities. What is important to note is the existence of a “price”. The same principle applies to electricity, it has a price that represents the cost of making electricity available to customers when for example, a light switch is flicked on. This price is called the electricity tariff, and in Nigeria, is determined by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC). In this article, we will look at the Nigerian electricity tariff methodology and electricity price cost components.

The Customer Tariff Methodology

A tariff methodology is simply the procedure or steps applied in the calculation of a tariff or the calculation steps in determining tariffs. According to the Electric Power Sector Reform Act (EPSRA) 2005, NERC must abide by the following key objectives when setting end-user tariffs:

- Make prices fair to consumers.

- Ensure that prices allow the licensees/commercial stakeholders to finance their activities.

- Ensure that prices allow the licensees/commercial stakeholders to make a reasonable profit for efficient operation.

- Ensure that the licensees/commercial stakeholders with efficient operations recover the full cost of their business activities and earn a reasonable return on capital invested.

- Ensure that stakeholders are encouraged to improve their technical and economic efficiency and the quality of services they provide.

Based on these principles, NERC has adopted an incentive-based tariff methodology for the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry (NESI). An incentive-based approach seeks to reward performance above certain set benchmarks in a bid to encourage improved outcomes, for example, certain organisations reward their staff with bonuses for achieving sales targets. NESI’s tariff methodology can be categorized into three (3) major building blocks, which are:

- Allowed Return on Capital – This is the interest recovered on the capital investment made by an investor. For example, the cost of buying a transformer.

- Allowed Return of Capital – This is the recovery of the capital invested in buying infrastructure or building/developing the infrastructure. For example, the depreciated cost of the purchased transformer.

- Efficient Operating Costs and Overheads – This is the actual cost the business incurred in providing services to customers. For example, the staff and maintenance costs associated with the transformer.

Operating as a licensee in the electricity sector is capital intensive requiring significant ongoing investments in power equipment and infrastructure, and operational expenses for service delivery. Therefore, to remain profitable, the income streams of a licensee business should provide a return of capital, a return on capital, and efficient operating costs and overheads to ensure it can operate efficiently.

A prudent recognition of these costs in the tariffs enables licensees to guarantee a stable and reliable electricity supply, which ensures customer satisfaction and incentivizes licensee investors to continue investing. As a result, NERC is legally responsible for protecting the interests of customers and licensees operating in NESI, ensuring that tariff components are determined fairly and efficiently and that the price paid for power is commensurate with the quality of service received.

With the three (3) building blocks, NERC sets a tariff for the end-user that consists of the entire value chain costs involved in providing electricity. These include generation, transmission, distribution, and administrative costs. Along with these costs, NERC also applies macroeconomic, grid performance, and energy supply assumptions to the tariff. Some of the assumptions include:

- Nigerian Inflation/US inflation

- Foreign exchange rate – (Naira/$)

- US consumer price index (CPI)

- Weighted Average Cost of Capital

- Gas price

- Generation capacity

- Energy generated

- Aggregate Technical Commercial & Collection losses (ATC&C) – Electricity Losses

The assumptions mentioned above will be addressed in Part 5 of our tariff series. In this article, the key focus is on the costs.

Costs in the NESI

There are three main sectors in the NESI value chain: generation, transmission, and distribution. The costs attributed to each of these sectors are contained in the end-user tariff. Apart from these costs, the regulator and supporting agencies with administrative functions also have embedded cost components in the tariff.

A. Generation Cost

There are two main costs in the generation sector of the NESI value chain:

- Capacity charge

- Energy charge

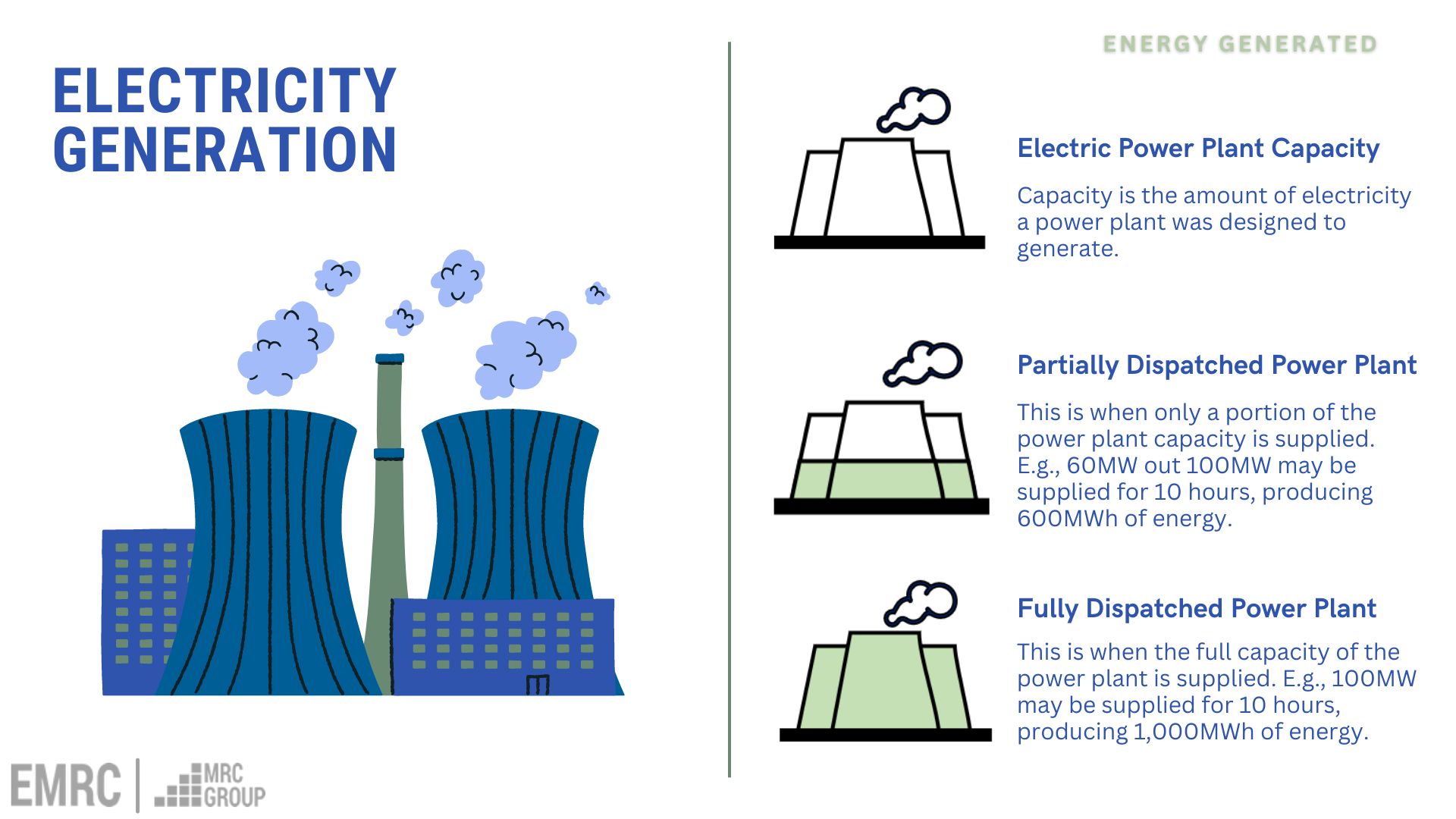

Electricity generation tariff is made up of 2 components, capacity, and energy. Capacity, denominated in Megawatts (MW), is the amount of electricity a power plant was designed to produce, while energy is the amount of electricity the power plant produces within a given time denominated in Megawatt hours (MW/h).

The capacity and energy charge account for two different things.

To illustrate this difference, let’s assume I patronise a car hire service that charges a fixed fee for renting a car and an hourly service fee for using a driver. If I spend 6 of those hours at work, it means I can only be driven for 2 hours. Therefore, I will pay the fixed fee representing the car’s availability for 8 hours but will only pay for using 2 hours of the driving service. The fixed fee is similar to the capacity charge while the service fee I pay for using the driving service is the energy charge.

The capacity charge compensates the Generation Companies (GenCos) for the portion of their power plant that is made available to generate electricity at any time while the energy charge covers the actual amount of electricity that is generated and sent out of the plants.

B. Transmission Cost – (Includes Regulatory & Administrative Charges)

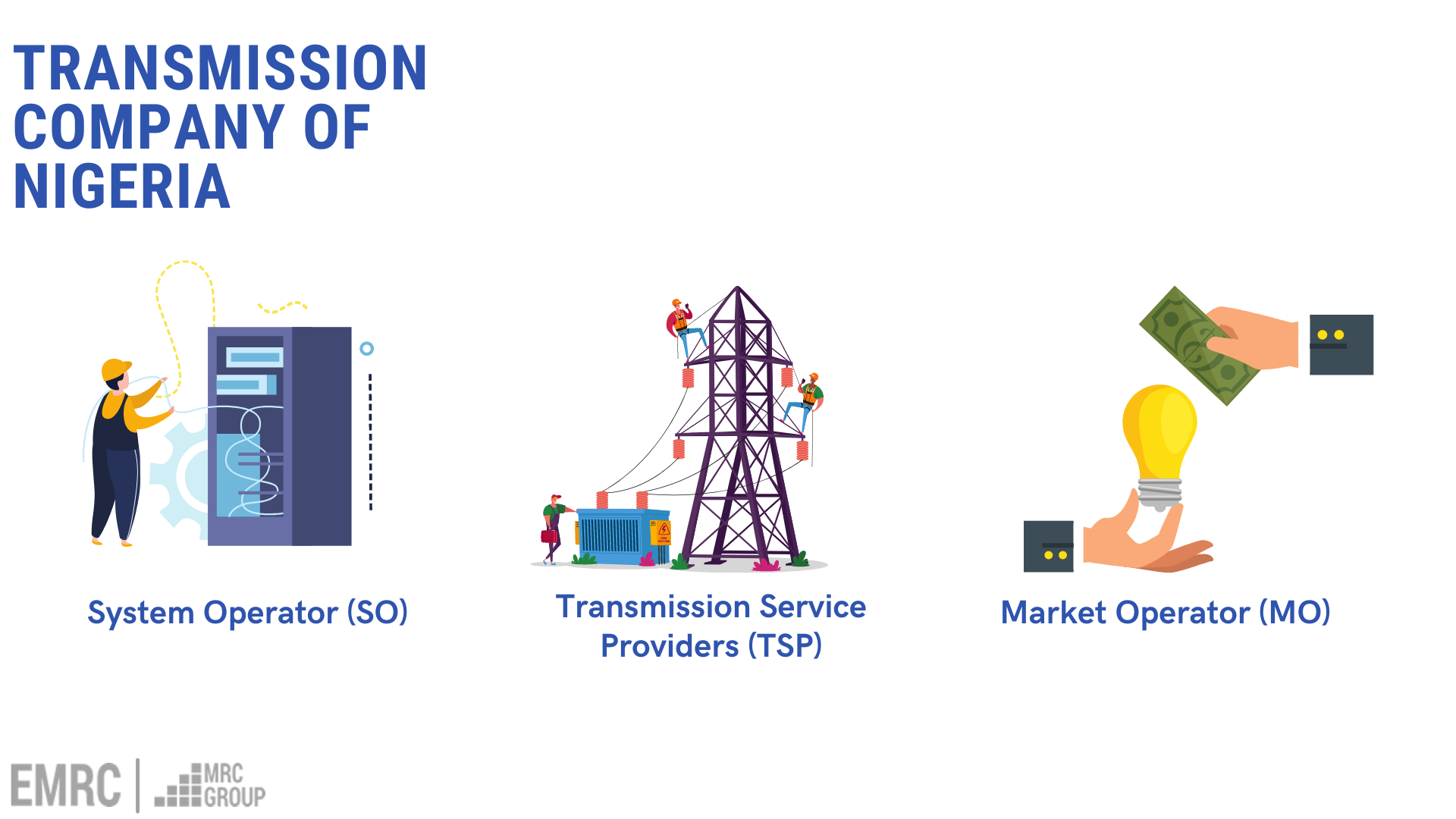

The transmission sector of the value chain consists of one government-owned entity which enjoys a monopoly over the ownership and operation of electricity transmission infrastructure in the NESI, called the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN). TCN is made up of 3 key divisions with different functions: the Transmission Service Provider (TSP), the Market Operator (MO), and the System Operator (SO).

- Transmission Service Provider (TSP)

The TSP manages the expansion and maintenance of electricity transmission grid infrastructure, which includes power lines and substations that make up the transmission division of the national grid. For its services, it receives a Transmission Use of Service (TUOS) charge.

- Market Operator (MO)

The Market Operator (MO) serves as a commercial administrator in the NESI. It is responsible for creating and administering the Nigerian Electricity Market Rules and serves as a collection point for administrative and regulatory charges in the NESI. It collects payments on behalf of the TSP, SO, NERC, and the Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading (NBET) Plc

(NBET buys electricity in bulk from the GenCos and sells it to the Distribution Companies (DisCos)). The MO also collects charges for Ancillary Services (AS) (administered by the SO) which are a variety of technical operations that ensure safety and stability in the grid by maintaining a proper balance of electricity demand and supply, keeping electricity frequency and voltage within safe limits, and preventing grid overload. Lastly, the MO collects charges for its functions which include drafting, implementation, and enforcement of the Market Rules, administration of the commercial metering system, administration of the NESI payment system, and ensuring NESI stakeholders comply with the grid code.

- System Operator (SO)

The System Operator (SO) serves as a technical administrator for the national grid. It oversees and is compensated for services including generation scheduling, commitment & dispatch; transmission scheduling and generation outage coordination; transmission congestion management; international transmission coordination; procurement and scheduling of ancillary services, and system planning for long-term capacity expansion.

C. Distribution Cost

Costs in the distribution sector are primarily operational expenditure (OPEX), and capital expenditure (CAPEX). These two components include the revenue required for DisCos to provide a reliable power supply and make the required investments for efficient service delivery.

To illustrate, the costs of fuelling, replacing faulty car parts and employing drivers by a car hire service represent its OPEX, which it includes in its service fees. Its CAPEX provision will include the purchase of a new car, which it includes in its fixed fees.

With the OPEX allowance in the tariffs, DisCos can maintain their distribution infrastructure, provide metering and billing services, collect payments, access insurance, and perform other operational, and maintenance tasks to support service delivery.

The tariff CAPEX provision recognises the investments made by Discos for network expansion and upgrades to provide a reliable power supply to customers. CAPEX is usually associated with expenditures on long-term assets like infrastructure, machinery, and vehicles.

As one can imagine, various companies have different OPEX, and CAPEX requirements and the same principle applies to electric utilities. They all have different OPEX and CAPEX requirements. Therefore, costs differ amongst DisCos, which is one reason, a recognizes, why customer tariffs are not identical across all utilities.

C. Allowed Electricity Losses

As electricity is transmitted and distributed using lines and wires, some of it is lost in the form of heat energy. This is an unavoidable physical phenomenon known as technical losses, which occur in every power system globally. The two other main losses which are more prominent in distribution systems of developing economies include commercial and collection losses.

Commercial losses are due to differences between energy sold and billed by Discos typically due to energy theft while collection losses occur due to a failure to collect full payment for energy from customers.

Consequently, the customer tariff includes a loss component to compensate distribution utilities for their losses. Electricity regulators usually allow a certain level of aggregate technical commercial and collection (ATC&C) losses in tariffs to reflect a reasonable component of system energy losses which is beyond the control of distribution utilities.

The ATC&C losses are typically reviewed downward annually by NERC to encourage the adoption of efficient practices by Discos to reduce their losses. The total costs Discos can recover as revenues are determined by their actual loss performance. If the regulator allows a cost of losses of N10 but the distribution utility incurs a cost of losses of N25, the utility makes a loss of N15. To perform profitably, the Disco’s loss performance will need to match it is allowed losses.

Conclusion

An electric utility aims to efficiently provide services and make a reasonable return on its investments, and electricity pricing plays an important role in achieving these goals. With unrealistically low prices, utility investment may be threatened, leading to poor service delivery and customer dissatisfaction. Likewise, with overestimated prices, customers will be dissatisfied. The level of customer dissatisfaction will be worsened if the prices do not reflect the quality of service and there is inadequate information about upward review in electricity prices. For regulators, particularly in the current global economic downturn, striking the pricing balance of fairness and simplicity to customers and providing a proper return to investors, is made more difficult by escalating value chain costs of providing reliable electricity.

To a reasonable extent, the NESI customer tariff methodology is fit for purpose. None of the costs in the customer tariff is arbitrary, and the use of the incentive-based tariff methodology effectively strikes a balance between the protection of customers’ interests and the interests of distribution licensees. Nevertheless, NESI is not without its challenges, ranging from inadequate supply to frequent grid collapses and suboptimal performances by Discos.

These issues are also cyclical in nature, as poor operations by Discos means they cannot fully recover the costs required to settle the entire value chain, thereby discouraging investments in new generation and network infrastructure needed to guarantee reliable power supply.

“But if the tariff methodology is fit for purpose, how come I don’t get constant electricity supply?”

is a thought we believe will be on the minds of our readers. As part of this ongoing tariff series, we will try to answer questions about cost-reflectivity and quality of service, and also discuss the evolution of electricity tariffs in NESI.

This is a good write up & is expository.

However, my question is how do you calculate the Disco loss performance